These notes show my personal learning and interpretations, and they are not official documentation from Microsoft. The goal is to offer a deeper look into how X++ code, the compiler, and the runtime work in Dynamics 365.

Where is the X++ code stored in the file system?

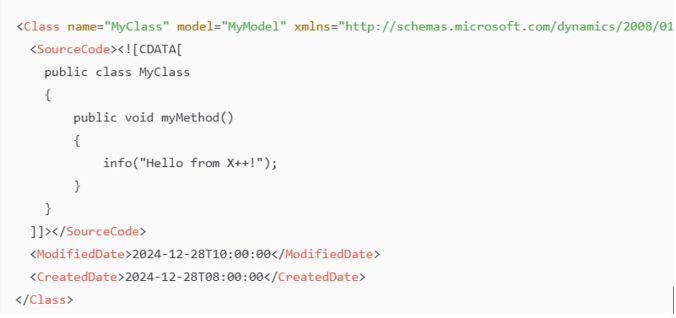

X++ code resides in XML files that define classes, tables, forms, and other objects. These files are part of the application model’s metadata and appear in Visual Studio as X++ objects.

Class Definition: Found as an XML file under \Classes\MyClass.xml.

Table Definition: Found as an XML file under \Tables\MyTable.xml, listing fields, methods, etc.

In a D365 10.0.42 codebase, the PackagesLocalDirectory contains approximately 542,091 files (about 17.69 GB). Of these, around 340,029 are XML files, representing the AOT (Application Object Tree).

What are the relationship between Models and Packages ?

All code is placed into a model, which is essentially a design-time logical grouping of metadata and source files. You can see them on disk in a path like:

D:\AOSService\PackagesLocalDirectory\Application\Metadata\MyModel\Classes\MyClass.xml

Here,

- ModelName = MyModel

- ObjectType = Classes

- ObjectName = MyClass.xml

There are 171 models in the standard Microsoft codebase. Each model belongs to a package, which serves as the compilation and deployment unit. You can combine one or more packages into a deployable package for runtime.

Example

The Application Suite model is the largest one, with 185,939 XML files, totaling 1.32 GB.

Compilation Output and .NET Components

Compiling X++ turns the application artifacts (X++ code, metadata, and resources) into deployable and executable components in .NET Intermediate Language (IL), which run under the CLR (Common Language Runtime). The compilation produces:

- .dll files (the main assemblies)

- .netmodule files (modules containing the IL code for X++ types)

- .pdb files (debugging symbols, used primarily in development environments)

- .md files (runtime metadata)

.netmodule files hold the actual IL code for each X++ type. If you open a form like SalesTable, all the required .netmodule files for that form must also be loaded.

.md files contain runtime metadata, classified by type (Class, Table, Form, etc.). They include only the essential metadata required at runtime (e.g., control hierarchies, table relationships), in contrast to the comprehensive XML files that exist only at design time. As a result, XML files are excluded when you deploy to sandbox or production.

.pdb files are for debugging and are not typically deployed to production.

How the Compilation Process Works

X++ code is first compiled into .netmodule files. The .netmodule files are then linked together to produce the final .dll file for the package. The .pdb file is generated alongside the .dll and holds debugging metadata.

The .netmodules also allows for incremental compilation, and you will thus often see multiple .netmodules files generated. But when you compile the entire smaller module, you will see that the .netModules are typically returned to one file. But for larger modules, like the Application Suite you can see that there are 276 .netmodules files. I suspect there are a limitation or optimalization to have the Application Suite splitted into multiple files.

Runtime Execution and Loading Behavior

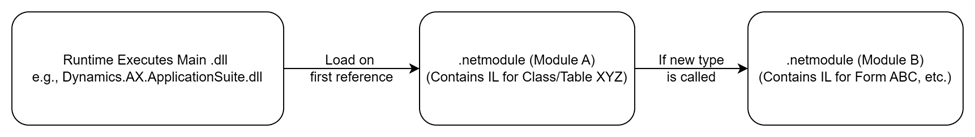

When the system needs to run code:

- The main .dll (e.g., Dynamics.AX.ApplicationSuite.dll) is loaded first.

- The .netmodule files containing the needed X++ types (classes, forms, etc.) load on demand.

The runtime loads a specific .netmodule only when a type within it is first accessed. The first load includes overhead, such as initializing event handlers and chain-of-command (CoC). Subsequent calls to types in the same .netmodule do not incur the same cost.

How does this affect runtime behavior in relation to Cold vs. Warm Start

I guess most of us have experienced performance difference between cold and warm starts, and this is caused by runtime behaviors involving .netmodule files and object initialization.

At cold start:

When a class or object is accessed for the first time after an AOS restart, the runtime loads the .netmodule containing the class/object into memory. Static constructors and chain-of-command/event handlers are initialized and metadata required for the type is fetched and cached.

This initialization process can take significant time, especially for larger .netmodule files or types with complex dependencies.

To further explain, when opening the salesTable form can take up to 30s, as there are a lot of tables, classes, form elements that needs to be loaded also. And each of these may have extensions event handlers and chain-of-command. This results in an enormous amount of files to be accessed, loaded and initiated. In short, a domino effect of loading executable .netmodules happens. If you take a look at SalesTable, you realize the number of tables, extensions, modules and code that is packed together on a single form. I have not tried to understand or count the number of elements that go into loading this form, and here just showing number of extensions and tables you see in an extension of the Sales Table form.

During runtime, the system also builds and populates various caches (e.g., metadata, plugin, and event handler caches). Cache population may traverse large amounts of metadata, contributing to the cold-start delay.

At warm start:

After the .netmodule and associated handlers are loaded into memory, subsequent references to types in the same .netmodule are faster because the .netmodule is already in memory and metadata and handlers have been initialized. Opening the salesTable drops from 30s to 3.5s.

How about the Azure SQL?

While some suspect Azure SQL for cold-start delays, the database typically performs very well and is not the main culprit for slow cold starts. For example, inserting 10,000 records via a SQL script might take only 143 ms, whereas inserting them through X++ can average 10,000 ms—largely due to latency and transactional overhead on the AOS side, not the database itself.

So the conclusion is that it makes no sense to blame the SQL for cold start performance issues. The actual reason is the object loading and initiation of assemblies and .netmodules just takes time.

Word of advice

- Reduce AOS restarts/deployments: Every AOS restart triggers the same loading and initialization of .netmodules and IL.

- Test performance on a warm system: Always measure performance after the first load.

- Implement a warm-up script: Access your most-used forms (SalesTable, PurchTable, CustTable, etc.) automatically on each AOS to reduce cold-start delays.

- Avoid blaming Azure SQL: The real delay is in loading .netmodule files and initializing CoC/event handlers.

- Adding more AOS instances may not help. Each AOS must still load and cache everything. As a result, more AOS instances could increase overall warm-up demands, and more users will be affected by the cold system syndrome.

References For official documentation on X++ and model architecture, consult Microsoft Learn: X++ Programming and other related Microsoft documentation.

Pingback: Hello World in Microsoft Dynamics 365 Finance and Operations D365FO X++ – TRJHTECH